Women academics and work-life balance in the UK: My personal perspective

Dr Clara Cheung

Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) in Project Management in the Department of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering at the University of Manchester, United Kingdom

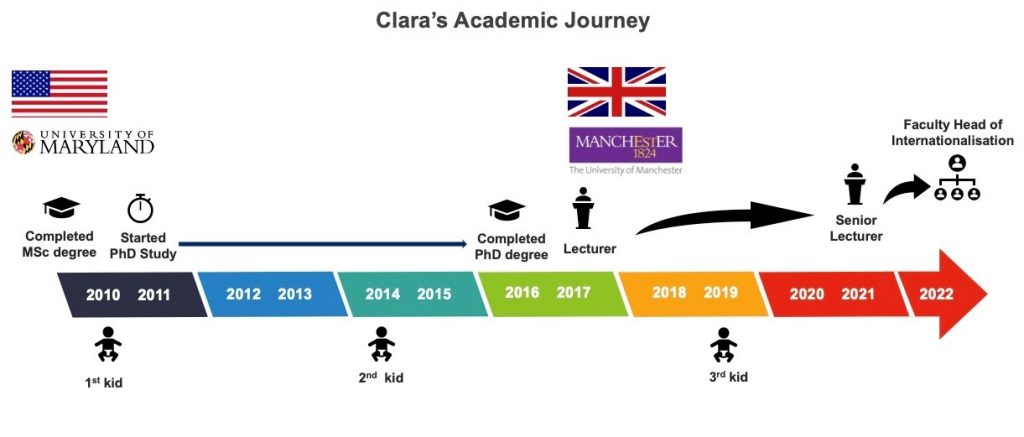

After spending almost a decade working in Fortune 500 companies on supply chain management in the Asia Pacific region, I went to the United States for my post-graduate studies in 2008 to reunite with my Japanese husband who studied for his PhD degree. Since then, I completed my MSc (2010) and PhD (2016) in Civil Engineering at the University of Maryland while I gave birth to my first two kids. In 2017, I started working as a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Project Management in the Department of Aerospace, Mechanical and Civil Engineering at the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom and got promoted to Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) in 2021, and to Faculty of Science and Engineering Head of Internationalisation for ASEAN, Japan and Korea in 2022. In between all these duties and promotions, I gave birth to my third kid in 2019.

As an academic who is on a research and teaching track, my role involves generating research publications, obtaining research grants and delivering related projects, supervising students at all levels, teaching, marking, working on administration duties, and carrying out various leadership roles internally and externally to help build professional esteem as well as implementing university’s strategies. It is not surprising that research indicated academics in the UK higher education are significantly more likely than non-academics to experience higher levels of stress because of long working hours and work overload (e.g., Fontinha et al., 2019). Although academic careers do provide a large degree of flexible working hours, it could also lead to conflict with work, which often spills over into the non-work domain (e.g., family and personal life) due to the inability to separate the domains (e.g., Segal, 2014). Research also revealed that women academics experience a greater level of work-life conflict than men due to the impact of childcare responsibilities and being the primary homemaker (e.g., Eze, 2017), which is one of the main reasons leading to slower career progression than men (e.g. Currie and Eveline, 2011).

Having three kids and working as a full-time academic who wants to progress in my career, I also found it difficult to strive for a work-life balance although I am a researcher in occupational health, safety and well-being by profession. Yet, I would like to thank Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for inviting me to write an article about work-life balance so that I can do a self-reflection and share how the implementation of Athena Swan Charter in the UK affects the work-life balance of women academics in higher education as well as my personal experience in managing work-life balance.

Athena Swan Charter

Established in 2005 in the UK, Athena Swan Charter is a framework and accreditation scheme used to encourage and recognise commitments to advancing the careers of women in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine (STEMM) employment in higher education. Higher education institutions can be accredited in three award levels (i.e. bronze, silver and gold) depending on their level of commitment to gender equity and the related evidence such as progression and promotional data, uptake of training, awareness and use of flexible working and maternity leave policies, etc. Institutions also need to create action plans to enhance the identified improvement areas for their accreditation. To encourage institutions accredited by Athena Swan Charter, research councils and some funders in the UK require them to obtain the Athena Swan award so as to fulfil the grant application requirements. Under this circumstance, many higher education institutions in the UK were accredited by Athena Swan Charter. Although pieces of evidence showed it has brought some positive changes in gender equity, however, the genuineness of these positive changes has also been challenged due to a lack of reliable measurement of implementation (Rosser et al., 2019). Caffrey et al. (2016) and Ovseiko (2017) discovered that women academics were disproportionately responsible for most of the Athena Swan work compared to their male counterparts and thus resulting in a significant increase in their workload, which affect their work-life balance. My personal experience is that Athena Swan Charter does put pressure on the university to be more supportive towards the development of women academics through various human resources policies and mentoring schemes, which support work-life balance and career progression. For example, when I returned from my maternity leave, the Athena Swan Charter committee member from my university contacted me to talk about the support I received during my leave, ways to improve the arrangements, as well as the support I could get from the university for my return to work.

Personal lessons learned on managing work-life balance

Although it is not easy to strike a work-life balance as a woman academic who has kids, I summarise the following three key lessons learned that help me to manage it:

1.Understand and utilise the work-life balance policies in your institution

When I joined the University of Manchester in 2017, I already had two kids and one of them was still at the age of going to nursery. I utilised the on-campus nursery facility which saved me a lot of time from dropping and picking up my kid. To cope with the childcare demand of my third kid, on top of the maternity leave, I used shared leave and flexible work arrangements so that my husband could stay home to take care of the child on paid leaves, and I could change my teaching time to cater for my childcare responsibilities. Based on all these experiences, I think it is important to understand the work-life policies offered by your institution so that you could plan and utilise them accordingly.

2.Focus on managing your energy, not just your time

To manage your energy not just your time means to understand that your energy is renewable, whereas time is a finite resource. You can work more productively by investing in your physical and emotional well-being and taking breaks to refresh rather than draining yourself with long hours. Consider how much energy it takes to finish a task rather than how much time it requires. When you focus on energy management over time management, you can better balance your workload with your personal energy. If you are interested in how to manage your energy, I would highly recommend you to read the article, titled “Manage your energy, not your time” written by Tony Schwartz and Catherine McCarthy.

3.Build a support network

It is also important to build a support network of others that can help you. Some people might think it is a sign of weakness to ask for help, but I think that is not true. If there comes a time when it seems impossible to get everything done, be kind to yourself—ask for help. An effective support system includes emotional, physical, and professional support from co-workers, friends, family, and certified professionals. For example, when your child is sick and requires you to stay home to take care of him/her, it would be very helpful if you know a co-worker who is willing to cover your work for a while. A support system is not something that comes naturally. It requires a bit of effort to build and maintain, but I think the benefits are well worth the effort.

Author’s Bio

Dr Clara Cheung is a Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) in Project Management in the Department of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering at the University of Manchester, United Kingdom. With her mixed business and engineering educational background, she has conducted interdisciplinary research by applying organisational psychology, data science, and engineering management theories to tackle occupational health, safety, and well-being issues in high-risk industries. Her research has been funded by professional bodies, the UK government, charities, and private companies. Before being an academic, Clara spent nearly a decade working in Fortune 500 companies and led a vast number of organisational change and IT projects that improved product design, production efficiency and operational safety. She experienced working in Australia, China, Japan, India, and the USA.

References:

Caffrey, L., Wyatt, D., Fudge, N., Mattingley, H., Williamson, C., & McKevitt, C. (2016). Gender equity programmes in academic medicine: a realist evaluation approach to Athena SWAN processes. BMJ Open, 6(9), e012090. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012090

Currie, J., & Eveline, J. (2011). E-Technology and Work-Life Balance for Academics with Young Children. Higher Education, 62(4), 533-550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9404-9

Eze, N. (2017). Balancing Career and Family: Then Nigerian Woman’s Experience (PhD). Walden University.

Fontinha, R., Easton, S., & Van Laar, D. (2019). Overtime and quality of working life in academics and non-academics: The role of perceived work-life balance. International Journal of Stress Management, 26(2), 173-183. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000067

Ovseiko, P., Chapple, A., Edmunds, L., & Ziebland, S. (2017). Advancing gender equality through the Athena SWAN Charter for Women in Science: an exploratory study of women’s and men’s perceptions. Health Research Policy And Systems, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017- 0177-9

Rosser, S., Barnard, S., Carnes, M., & Munir, F. (2019). Athena SWAN and ADVANCE: effectiveness and lessons learned. The Lancet, 393 (101710), 604-608.

Segal, J. (2014). A South African perspective on work-life balance: a look at women in academia (PhD). University of the Witwatersrand.

Schwartz, T., & McCarthy, C. (2007). Manage your energy, not your time. Harvard business review, 85(10), 63.